2025-06-19 05:05:09

2025-06-19 05:05:09

2025-09-18 09:53:21

Honestly, Freedesktop has done so much more for the Linux ecosystem.

I don't know why we bother mentioning GNU at this point, since their contributions are ancient and small at this point. What is left is GCC and Glibc. Glibc being a source of pain more than being helpful.

GNU stuff is at the foundation of the Linux desktop, but not much more than that.

2025-09-17 02:00:58

I think I really need to sleep.

This font is weird...

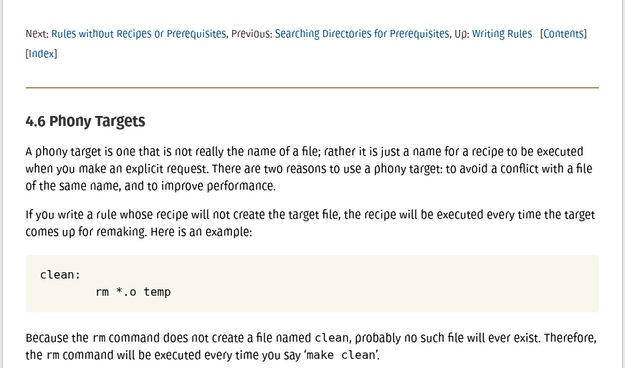

https://www.gnu.org/software/make/manual/html_node/Phony-Targets.html

2025-07-13 20:38:29

2025-09-15 16:13:12

2025-08-13 12:25:23

I got a Thinkpad x270 at a great price a few months ago, and the Arch Linux & i3wm combo makes it work great.

Their reputation for working well with GNU/Linux systems is well deserved.

If you are looking for alternatives for your computer equipment, the second-hand market offers this and other classic models at a very good price in almost every corner of the globe. And when the second wave of equipment arrives thanks to Windows 11, this is going to be amazing.

2025-08-30 07:08:36

gcc now has builtin functions for CRCs https://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/CRC-Builtins.html

2025-07-09 12:52:34

2025-07-08 09:33:13

I read this just to check they're not adding an LLM to bash.

Yet.

https://www.omgubuntu.co.uk/2025/07/bash-5-3-new-features

2025-08-05 21:49:23

Somebody saved Progeny Debian 1.0, and it's available to download here! https://erdincay.github.io/progeny-debian-linux/

2025-08-14 20:04:24

New on #Quansight PBC blog: Python Wheels: from Tags to Variants

#Python distributions are uniform across different Python versions and platforms. For these distributions, it is sufficient to publish a single wheel that can be installed everywhere. However, some packages are more complex than that; they include compiled Python extensions or binaries. In order to robustly deploy these software on different platforms, you need to publish multiple binary packages, and the installers need to select the one that fits the platform used best.

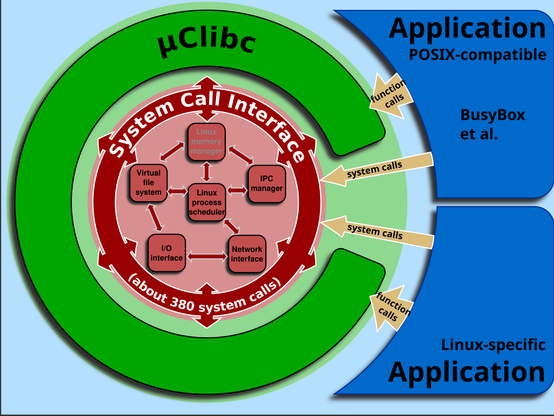

For a long time, Python wheels made do with a relatively simple mechanism to describe the needed variance: Platform compatibility tags. These tags identified different Python implementations and versions, operating systems, and CPU architectures. Over time, they were extended to facilitate new use cases. To list a couple: PEP 513 added manylinux tags to standardize the core library dependencies on GNU/Linux systems, and PEP 656 added musllinux tags to facilitate Linux systems with musl libc.

However, not all new use cases can be handled effectively within the framework of tags. To list a few:

• The advent of GPU-backed computing made distinguishing different acceleration frameworks such as NVIDIA CUDA or AMD ROCm important.

• As the compatibility with older CPUs became less desirable, many distributions have set baselines for their binary packages to x86-64-v2 microarchitecture level, and Python packages need to be able to express the same requirement.

• Numerical libraries support different BLAS/LAPACK, MPI, OpenMP providers, and wish to enable the users to choose the build matching their desired provider.

While tags could technically be bent to facilitate all these use cases, they would grow quite baroque, and, critically, every change to tags needs to be implemented in all installers and package-related tooling separately, making the adoption difficult.

Facing these limitations, software vendors have employed different solutions to work around the lack of an appropriate mechanism. Eventually, the #WheelNext initiative took up the challenge to design a more robust solution.

"""

#packaging

2025-07-14 12:31:29

2025-08-24 09:25:47

2025-06-28 21:28:08

I'd just like to interject for a moment. What you're referring to as OpenBSD, is in fact, GNU/OpenBSD, or as I've recently taken to calling it, GNU plus OpenBSD. OpenBSD is not an operating system unto itself but rather another free component of a fully functioning GNU system

2025-07-21 16:28:18

✨ System integrity check: passed.

Realization timestamp: [now].

Condition: You are #ActuallyAutistic.

Environment detected: #Debian GNU/Linux.

Result: ✅ Sensory environment = predictable

✅ Package manager = apt (non-chaotic, logical)

✅ Folder structure = m…