2025-12-12 19:24:39

Here's a photo that's a bit different from my usual style.

I took it with the tele lens on last weekend's hike. The inversion caused such a great sea of clouds with just some sole islands.

This kind of weather really offers such unique motives. And again: it was worth carrying the zoom lens up there :-D

Enjoy!

#photography

2025-12-13 10:00:04

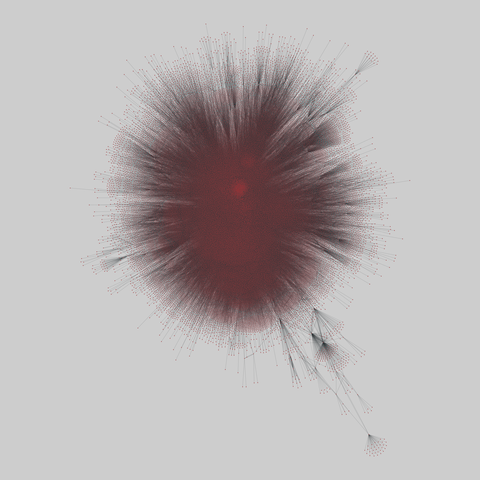

topology: Internet AS graph (2004)

An integrated snapshot of the structure of the Internet at the level of Autonomous Systems (ASs), reconstructed from multiple sources, including the RouteViews and RIPE BGP trace collectors, route servers, looking glasses, and the Internet Routing Registry databases. This snapshot was created around October 2004.

This network has 34761 nodes and 171403 edges.

Tags: Technological, Communication, Unweighted, Multigraph, Timestamps

2025-12-10 07:21:09

Australia's eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant says under-16s slipping through the cracks of the social media ban will be "booted off" the platforms in time (The Guardian)

https://www.theguardian.com/…

2026-01-13 12:02:54

Celebration de 75 annos con interlingua.

Jovedi le 15 de januario 2026, 19:00-20:20 UTC, 20:00-21:20 CET.

https://umu.zoom.us/j/63633002721?pwd=onf9kafi5UQN0ZXsiDwWmMiuwKce68.1

Zoom ID: 636 3300 2721

Contrasigno: 757575

Tres presentatione…

2025-12-10 07:25:55

Australia's eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant says under-16s slipping through the cracks of the social media ban will be "booted off" the platforms in time (The Guardian)

https://www.theguardian.com/…

2025-11-27 09:39:16

Real conspiracies tend to come out, but some of them take a while. Information on the Iran/Contra scandal broke out about 5 years after the conspiracy started. That would have taken several hundred people to carry out, so it was somewhat hard to hide. Even so, they largely got away with it.

The moon landing conspiracy theory would have taken thousands of people, so it would have come out more quickly. Since we have an example of a real secret program of a similar scale as what would be required to fake a moon landing (that is, the Manhattan project), we know that the fake moon landing conspiracy theory is not true. (There's also the literally tons of evidence in the form of rocks and other samples, and all kinds of other ways to debunk the claim.)

Could Kash Patel's FBI have been trying really hard to entrap people into carrying out terrorist attacks in order to justify #Trump's occupation of DC? Could they have helped a guy plan an attack then just failed to arrest him? There are reasonable scenarios that fall in between malice and incompetence while still indicating some level of false flag.

Could someone have just snapped and ambushed some guardsmen without any involvement from the FBI? Yeah, totally. The US is a country full of guns with a completely non-functional mental health system. Someone coming from a country that the US destroyed, twice, could have a lot of untreated trauma. Might they see the national guard as a threat (even if that wasn't totally true)? Yeah, they were deployed to threaten people (even when they were just picking up trash). The point was to incite this kind of response. It's completely reasonable to believe that the FBI would not need to be involved at all, that this would just be the stochastic response they were looking for.

So the point here is that everything is on the table, nothing is really known, nothing should be surprising, and no matter what it's Trump's fault. This is exactly the escalation he was looking for. If he didn't get it naturally, he would also have had ways of making it happen.

He will use this in exactly the same way as the Reichstag fire, to drive a wedge between liberals and radicals. Don't fall for it.

Edit:

There are plausible reasons to not believe the official narrative at all right now, or maybe ever. The official narrative is also plausible, but there are plausible reasons to disagree with the response even if the official story is true. It is unnecessary to resort to conspiracy thinking in order to account for what happened and to disagree with the response. But it is also understandable why someone might jump immediately to a conspiracy given the circumstances.

2025-11-13 00:00:08

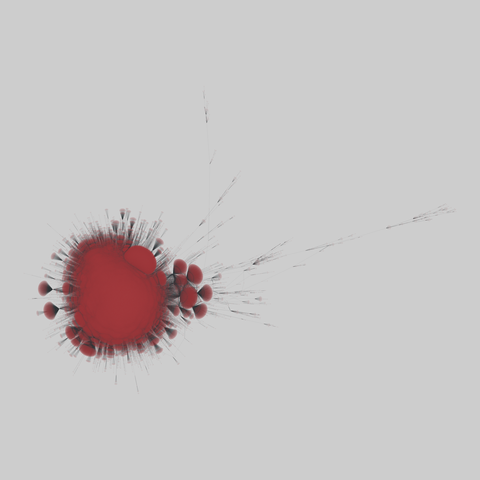

lkml_thread: Linux kernel mailing list

A bipartite network of contributions by users to threads on the Linux kernel mailing list. A left node is a person, and a right node is a thread, and each timestamped edge (i,j,t) denotes that user i contributed to thread j at time t. The date of the snapshot is not given.

This network has 379554 nodes and 1565683 edges.

Tags: Social, Communication, Unweighted, Timestamps

2026-01-10 06:05:51

Internal document: Amazon rolled out a manager dashboard that tracks employees' office attendance and how many hours they spend there, after its RTO mandate (Pranav Dixit/Business Insider)

https://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-flags-employees-rto-office-2026-1